Xuan Paper: A Millennium of Preservation,The Oriental Cultural Vein Flowing in Ink

Among the “Four Treasures of the Study” (writing brush, ink stick, ink stone, and paper) in traditional Chinese culture, Xuan Paper is hailed as the “King of Paper” and “Millennium-Lasting Paper” for its unique qualities: tough yet absorbent, smooth yet not slippery, pure white and dense, with a clean texture. Originating from Jing County, Anhui Province, this papermaking craft uses sandalwood bark and sand-field rice straw as raw materials, refined through hundreds of processes. It not only embodies the ancient Chinese pursuit of excellence in writing and painting but also condenses the wisdom of harmonious coexistence between humans and nature. Today, with its warm texture, it still conveys the unique charm of Chinese calligraphy and painting art to the world.

The history of Xuan Paper can be traced back to the Eastern Han Dynasty. After Cai Lun improved papermaking technology, traces of early papermaking appeared in the southern Anhui region. In the Tang Dynasty, Xuan Paper from Jing County began to gain prominence—”Yuban Xuan” (Jade Plate Xuan Paper) at that time was already a favorite among scholars and calligraphers. Li Bai, the “Poet Immortal”, once praised it in his poems: “The 300-li Jingchuan River makes Ruoye Stream feel ashamed in comparison.” In the Song Dynasty, the craftsmanship of Xuan Paper matured. Since Jing County was historically under the jurisdiction of Xuanzhou Prefecture, it was officially named “Xuan Paper” and became a tribute to the imperial court. The Ming and Qing dynasties marked the heyday of Xuan Paper: not only did its types expand (such as raw Xuan, processed Xuan, and semi-processed Xuan), but its craftsmanship also became more sophisticated. During the Qianlong reign, “Sajin Xuan” (Gold-Flecked Xuan Paper) and “Miaojin Xuan” (Gold-Traced Xuan Paper) combined Xuan Paper with decorative art, becoming exclusive paper for the royal family. By this time, Xuan Paper had been exported overseas along with Chinese calligraphy and painting art, becoming an important carrier of Oriental culture.

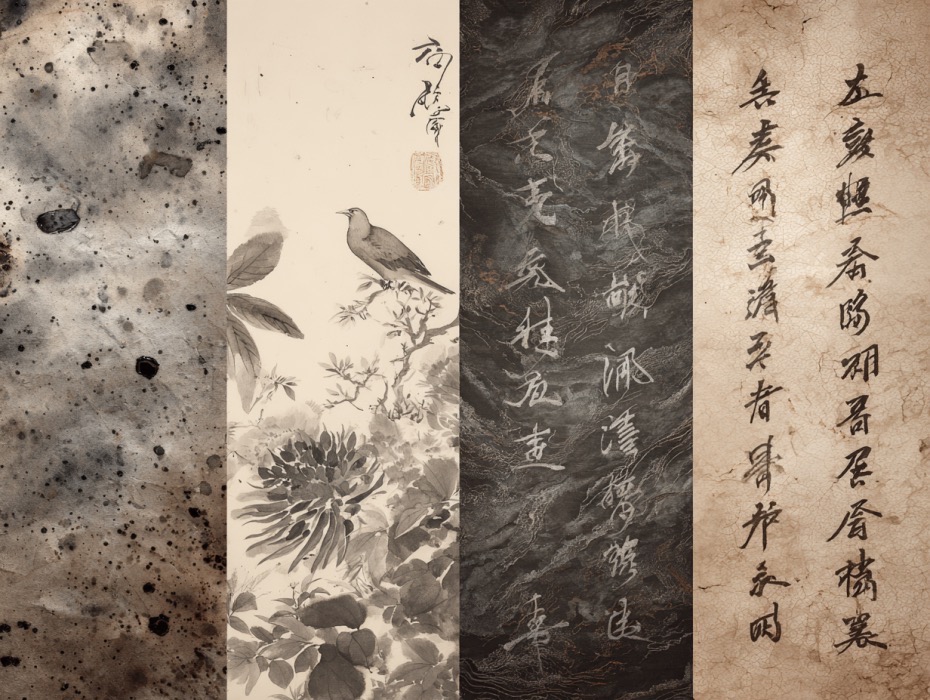

The charm of Xuan Paper first lies in its unique raw materials and strict production process. The core raw material, “sandalwood bark”, is only produced in Jing County and the surrounding mountainous areas. Its tough and elastic fibers are the key to Xuan Paper’s “anti-aging and moth-resistant” properties. When paired with the local unique sand-field rice straw (with fine fibers and low silicon content), after repeated soaking, boiling, and beating, a unique interwoven fiber structure is formed, endowing Xuan Paper with both toughness and water absorbency. From raw materials to finished products, Xuan Paper goes through “108 processes” and takes more than a year: sandalwood bark is harvested in spring, rice straw is soaked in summer, pulp is beaten in autumn, and paper is fished and dried in winter—each step must conform to seasonal changes. Among these, “paper fishing” is the core process: craftsmen hold a bamboo screen and gently dip it into the pulp tank, allowing fibers to evenly attach to the screen. A slight deviation in strength or speed will affect the paper’s quality. “Paper drying” requires slow drying on a specially made paper 烘焙 (baking frame), using natural sunlight and breeze to create the paper’s natural texture and warm luster. It is this “collaboration between humans and nature” that gives Xuan Paper the property of “remaining intact for a thousand years”—the Tang and Song Dynasty calligraphy and painting works on Xuan Paper preserved in the Palace Museum still retain their original colors after hundreds of years, confirming the reputation of “millennium-lasting paper”.

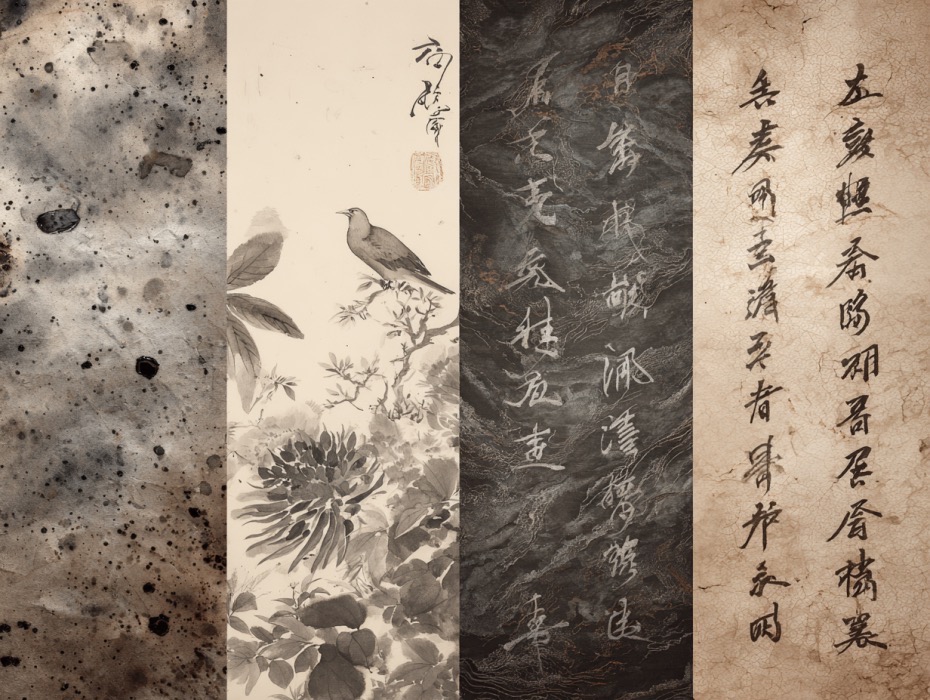

Xuan Paper has a wide variety of types, each adapted to different calligraphy and painting needs, forming a professional system of “one paper for one purpose”. Raw Xuan Paper has strong water absorbency and rich ink gradations; ink spreads immediately upon contact, making it suitable for writing running script, cursive script, or creating freehand landscape paintings. Painters can use the shade of ink to present the artistic conception of “splash-ink landscapes”. Processed Xuan Paper is treated with alum, resulting in weak water absorbency and stable ink color—it is suitable for meticulous painting and small regular script, as it can accurately present delicate lines and rich colors. For example, when painting flowers, birds, insects, and grass, every single hair can be carefully outlined. Semi-processed Xuan Paper falls between raw and processed Xuan Paper, with both absorbency and stability, making it suitable for writing regular script, official script, or creating paintings that combine meticulous and freehand styles. In addition, there are special Xuan Papers such as Sajin Xuan, Yunmu Xuan (Mica Xuan Paper), and Luowen Xuan (Ribbed Xuan Paper). By adding gold foil, mica, or pressing textures, they enhance the decorativeness of calligraphy and painting, meeting the needs of different creative scenarios.

Xuan Paper is not only a carrier for calligraphy and painting but also bears profound cultural significance. In Chinese calligraphy and painting art, the “ink-absorbing property” of Xuan Paper allows ink to have “five color changes” (burnt, thick, heavy, light, and clear). Painters can present rich layers with a single brush stroke—this “ever-changing ink charm” is irreplaceable by other papers. Scholars of all dynasties have regarded Xuan Paper as a spiritual sustenance. Masters such as Su Shi, Wen Zhengming, and Zheng Banqiao all left immortal works on Xuan Paper, making it a “living fossil” that records the Oriental cultural vein.

In modern times, Xuan Paper has not faded with the changes of the times but has gained new vitality through inheritance and innovation. On the one hand, traditional Xuan Paper craftsmanship is systematically protected: in 2009, the “Traditional Xuan Paper Making Technique” was included in the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Jing County has established Xuan Paper cultural parks and inheritance bases, where veteran craftsmen pass down core techniques such as paper fishing and paper drying to the younger generation through the “master-apprentice” model. On the other hand, innovations in Xuan Paper continue to emerge: craftsmen have developed Xuan Paper derivatives suitable for modern printing, such as Xuan Paper notebooks and Xuan Paper decorative paintings, bringing this traditional paper into daily life. At the same time, Xuan Paper has been integrated into contemporary art, becoming a material for installation art and performance art, endowing it with new artistic expressions. In addition, Xuan Paper has been repeatedly used as a “national gift” for foreign heads of state—for example, the “giant Xuan Paper calligraphy and painting” presented to the United Nations showcases the charm of Chinese culture to the world. In international art exhibitions, calligraphy and painting works on Xuan Paper have also won high praise, becoming a cross-border cultural symbol.

From the Tang Dynasty’s “Yuban Xuan” to the Ming and Qing dynasties’ “royal tribute Xuan Paper”, and to today’s modern Xuan Paper derivatives, Xuan Paper has always used fibers as a brush and time as ink to interpret the Chinese people’s pursuit of culture and beauty. It is not just a thin sheet of paper but a series of vivid historical memories and an enduring cultural heritage. In the new era, with its Oriental cultural vein accumulated over a thousand years, Xuan Paper transcends time, space, and national borders, telling the immortal legend of Chinese papermaking art to the world.