Tie-Dye: The Blue-and-White Poetry Woven in Warps and Wefts

Tie-dye, a traditional Chinese dyeing and weaving craft that uses needles as brushes, threads as ink, and dyes as colors, has written a millennium-long legend in the history of Chinese craftsmanship with its unpredictable patterns and fresh, simple style. It skillfully combines “restraint” and “bloom”, and each piece is an irreplaceable artistic creation. Not only does it carry the ancient people’s love for nature and life, but it has also become a cross-border aesthetic symbol in modern times, conveying the romance and vitality of the East to the world.

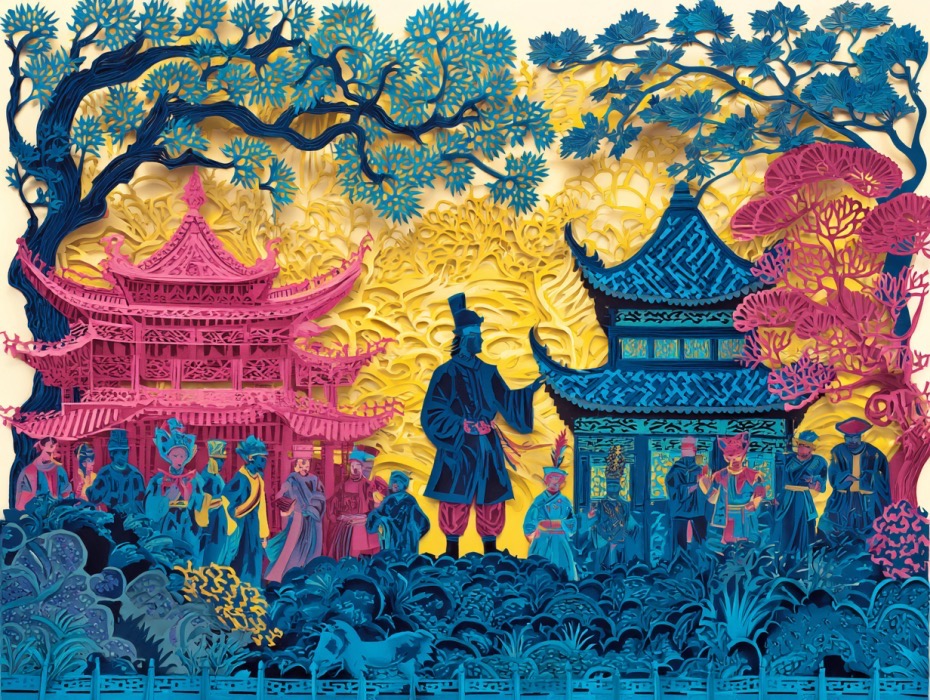

The history of tie-dye can be traced back to the Neolithic Age, when ancient ancestors began to dye fabrics with plant-based dyes. During the Warring States Period, the tie-dye craft initially took shape. Among the fabrics unearthed from Chu tombs, there were patterned fabrics made using the “jiaxie” technique (the ancient name for tie-dye). By the Tang Dynasty, tie-dye reached its prime: the craftsmanship became more exquisite, and the color patterns were richer. It not only became a high-quality clothing choice for royal nobles but also spread to Japan, Southeast Asia and other regions via the Silk Road, exerting a profound influence on local dyeing and weaving crafts. In the Song and Yuan Dynasties, tie-dye became widely popular among the people, especially in Yunnan, Sichuan, Jiangsu and other regions, forming unique local styles. During the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the tie-dye craft further developed. Patterns evolved from simple geometric designs to complex ones featuring flowers, birds, landscapes and more, achieving a perfect balance between practicality and artistry. Among them, the Bai ethnic group’s tie-dye from Dali, Yunnan, with its unique blue-and-white color scheme and exquisite craftsmanship, became a representative of tie-dye art and still maintains strong vitality to this day.

The charm of tie-dye lies in its unique craft that emphasizes “30% dyeing and 70% tying”, with every step full of ingenuity and unpredictability. The first step is “tying and binding”. Based on design concepts, craftsmen tightly tie, fold, wrap or clamp parts of white fabric with cotton threads, hemp ropes, etc., creating different folds and blank spaces. This step is the soul of tie-dye: the tightness of the binding, the angle of folding, and the thickness of the threads all directly affect the final pattern effect. Loose binding results in stretched patterns, while tight binding produces fine textures; random folding may lead to unexpectedly vivid designs. Therefore, no two tie-dye works are identical. The next step is “dyeing”. Traditional tie-dye mostly uses natural plant dyes, among which indigo made from isatis root and polygonum tinctorium is the most classic. This dye not only has a warm color but also possesses insect-proof and anti-corrosion properties. During dyeing, craftsmen immerse the tied fabric into a dye vat, repeatedly dipping and drying it to allow the dye to gradually penetrate the unbound areas, forming blue layers of varying shades. The final steps are “untying” and “rinsing”. After the fabric is dyed to the desired color, the bound threads are carefully removed, and the fabric is rinsed multiple times to remove excess dye. The previously bound parts then reveal the white base color, forming a striking contrast with the blue dyed areas. Various patterns such as ice crackles, cloud patterns and petal patterns “bloom”, as if created by the magical hand of nature.

China has a wide variety of tie-dye works with distinct regional characteristics, jointly forming a brilliant map of tie-dye art. The Bai ethnic group’s tie-dye from Dali, Yunnan is famous for its “blue-and-white dominated, concise and bright” style. It often uses ethnic characteristic patterns such as butterflies, camellias and landscapes, and the finished products are mostly daily necessities like clothing, scarves and tablecloths, full of strong life atmosphere. The tie-dye from Zigong, Sichuan is characterized by “rich colors and complex patterns”. In addition to traditional indigo, it also uses red and yellow dyes made from safflowers and gardenias. Its patterns mostly feature dragons, phoenixes and peonies with auspicious meanings, and are often used in artworks such as decorative paintings and folding screens. The tie-dye from Nantong, Jiangsu integrates the delicate style of Suzhou embroidery. Its patterns are exquisite and elegant, and it excels in showing the vitality of flowers and birds as well as the artistic conception of landscapes, enjoying a high reputation at home and abroad. In addition, the tie-dye works of ethnic minorities also have their own unique styles. For example, the Miao ethnic group in Guizhou combines batik with tie-dye, and the Zhuang ethnic group in Guangxi uses geometric patterns in their tie-dye, all reflecting the cultural characteristics and aesthetic pursuits of different ethnic groups.

In modern society, tie-dye has not faded with the changes of the times; instead, it has gained new vitality through innovation. On one hand, the traditional tie-dye craft has received systematic protection. Tie-dye inheritance bases have been established in various places. Elderly Bai craftsmen pass on the millennium-old craft to the younger generation through the “master-apprentice” model. At the same time, the government has enhanced the popularity and influence of tie-dye through applications for intangible cultural heritage status and cultural exhibitions. On the other hand, tie-dye has been deeply integrated with modern fashion, home decoration and cultural and creative industries. At international fashion weeks, designers incorporate tie-dye elements into high-end clothing—loose tie-dye sweaters and elegant tie-dye long skirts have become trendy items. In the home decoration market, tie-dye cushions, curtains and carpets inject a fresh and natural atmosphere into spaces. In the cultural and creative field, tie-dye notebooks, canvas bags and phone cases are deeply loved by young people, becoming fashionable carriers for inheriting traditional culture. Moreover, tie-dye has become an important bridge for cultural exchange. It has been exhibited in many international art exhibitions and cultural festivals, and many foreign tourists make special trips to Dali to learn tie-dye techniques, enabling this ancient craft to gain more love and recognition worldwide.

From simple dyeing in the Neolithic Age to its prime in the Tang Dynasty, and to its innovative development today, tie-dye has always taken fabric as paper, dye as color, and used the most simple craft to interpret the vitality and romance of Oriental aesthetics. It is not only a collection of exquisite fabrics but also a series of vivid historical records and an endless cultural inheritance. In the new era, with its unique charm, tie-dye is crossing time, space and national borders, spreading the blue-and-white poetry in warps and wefts to every corner of the world.